Winter 2024 (Volume 34, Number 4)

The Mini-Practice Audit Model (mPAM):

A Practical Guide to Analyzing and Applying the Data

By Raheem B. Kherani, BSc (Pharm), MD, FRCPC, MHPE; Elizabeth M. Wooster, M.Ed, PhD(c); and Douglas L. Wooster, MD, FRCSC, FACS, DFSVS, FSVU, RVT, RPVI

Download PDF

“I remember at the 2020 CRA Annual Scientific Meeting (ASM) in Victoria, just before the pandemic, we were all together and some of us went to the workshop on mini-Practice Audit Models (mPAM),” remarked Dr. AKI Joint, a rheumatologist member of the Canadian Rheumatology Association (CRA). I have data from my first analysis. It seemed easy then, but with so much that has gone on since the pandemic ended, I think I need a reminder. Maybe I’ll need to contact the CRA staff at info@rheum.ca to ask how I can get into the Member Portal to view the workshop slides from that specific workshop.”

The cycle of audit, analysis, education/intervention, application, re-audit and re-application used in the mPAM can be used for personal improvement or in a group strategy. Let us go back to the example with the 2018 systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Guidelines and cardiovascular risk assessment (Box 1).

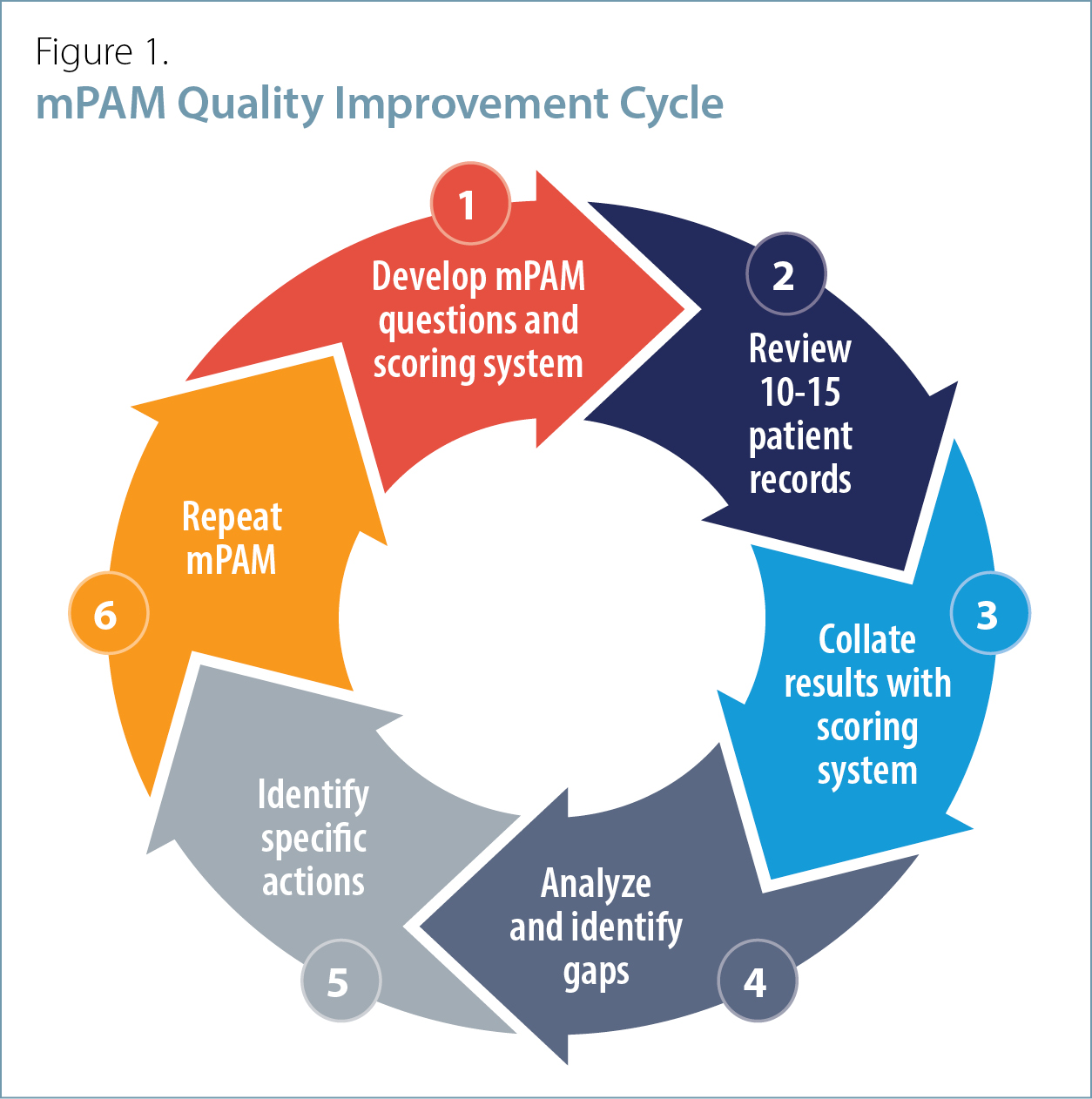

Figure 1 outlines the process of the mPAM cycle to collect the first and subsequent sets of data. By using a 1-5 Likert scale, we can assess our answers to the questions with 10-15 charts for the audit.

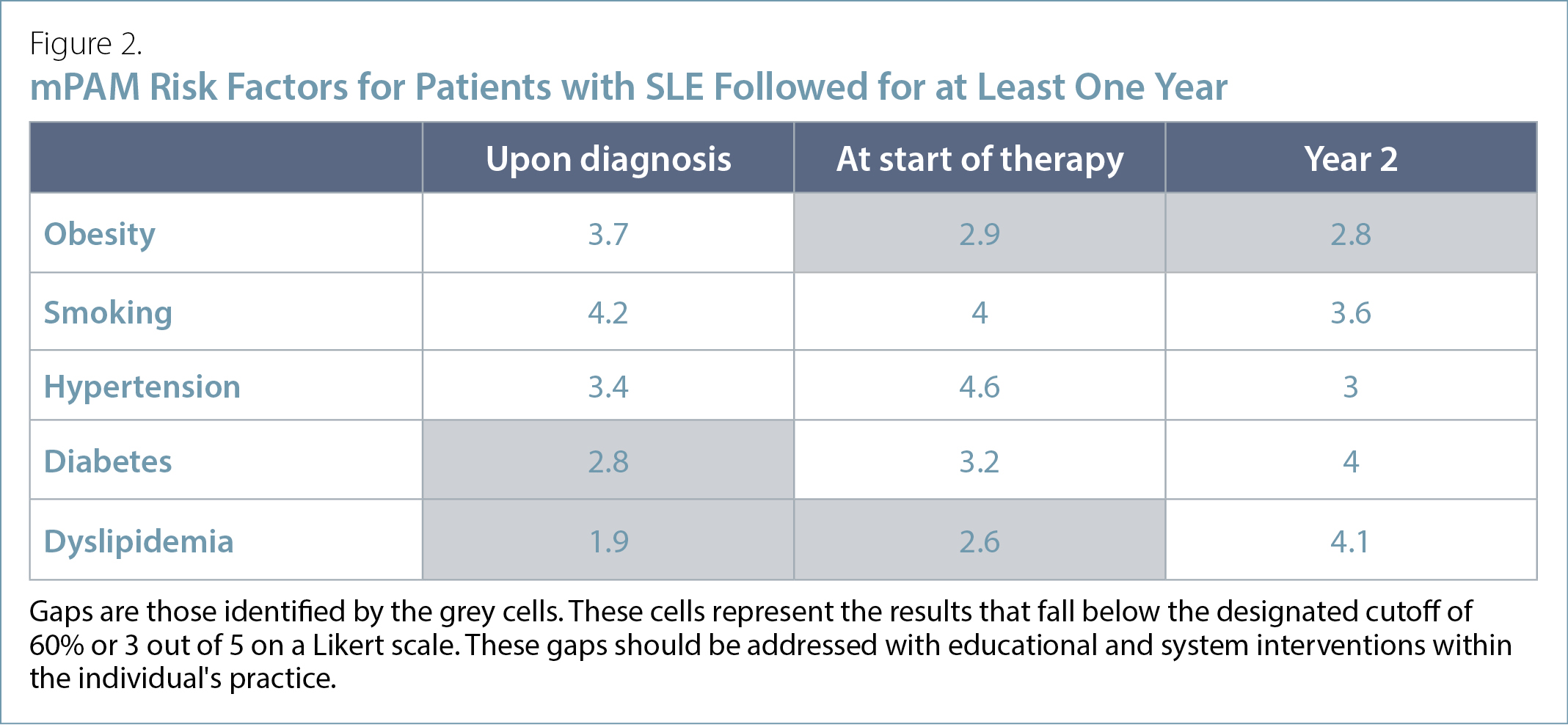

Following the initial audit (Figure 2), we can reflect and review opportunities for improvement. The grey cells show that there are opportunities to improve (scores below 3 out of 5) in diabetes, dyslipidemia and obesity identification.

In addition to educational resources in these clinical areas and understanding the reasons to refer the patient back to the primary care provider for cardiovascular risk factor management, we can take the opportunity to review resources in documentation and record keeping (www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/education-events/good-practices/physician-patient/documentation-and-record-keeping and www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/education-events/teaching-resources/physician-patient/documentation--principles-of-medical-record-keeping). The mPAM highlights that if we did not document this information, it did not happen.

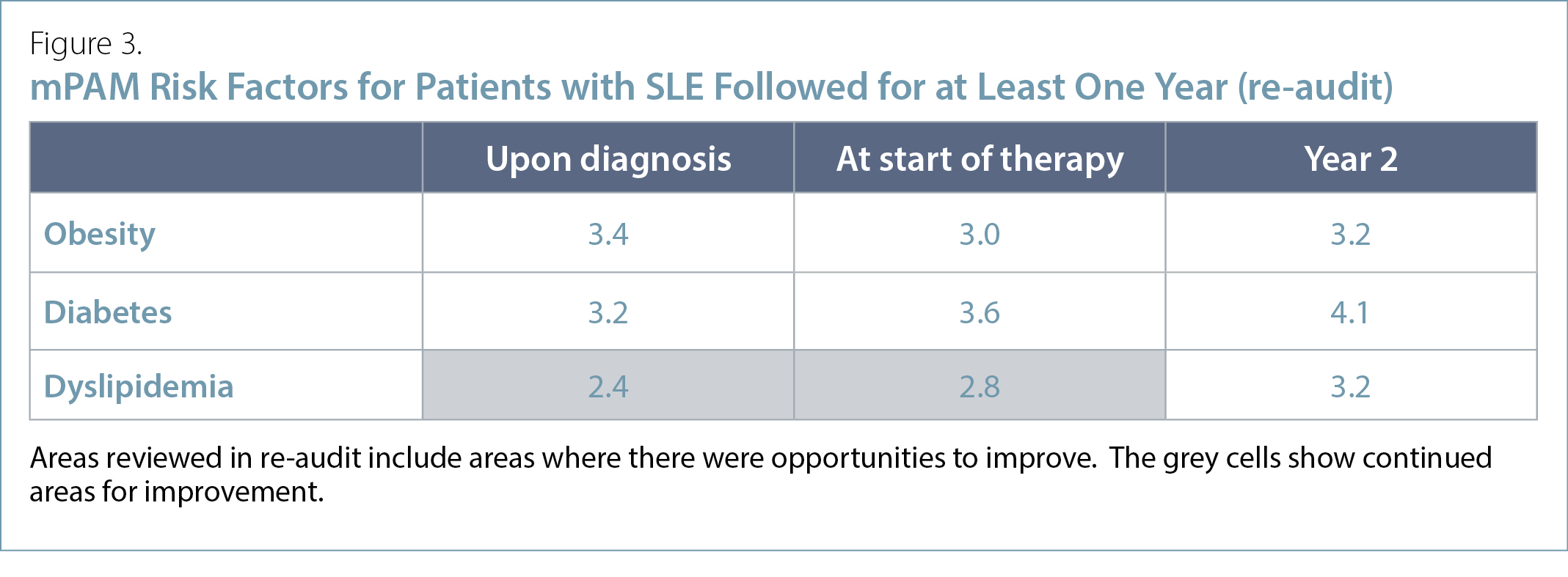

In three to six months, we can re-audit (Figure 3) and review the areas that need improvement. By carrying out these re-audits, we can continue to enhance our practice and expand to look at other areas that may benefit from this type of positive impact.

“The mPAM is practical and possible for me to do…” says Dr. AKI Joint. “I continue to apply these changes I have learned by my focused re-audits and continue to improve my patient care (and receive MOC Section 3 credits).”

Raheem B. Kherani, BSc (Pharm), MD, FRCPC, MHPE

CRA Education Committee Past Chair,

Program Director and Clinical Associate Professor,

University of British Columbia

Director, Intensive Collaborative Arthritis Program,

Mary Pack Arthritis Program

Clinician Investigator, Arthritis Research Canada

Division Head, Rheumatology, Richmond Hospital

Rheumatologist, West Coast Rheumatology Associates

Richmond, British Columbia

Elizabeth M. Wooster, B.Comm, M.Ed, PhD(c)

OISE/University of Toronto

Research Associate,

School of Medicine,

Toronto Metropolitan University

Douglas L. Wooster, MD, FRCSC, FACS,

DFSVS, FSVU, RVT, RPVI

Professor of Surgery,

Temerty Faculty of Medicine,

University of Toronto

Selected References:

1. Rose N, Pang DSJ. A practical guide to implementing clinical audit. Can Vet J. 2021;62:145-156.

2. Esposito P, and Dal Canton A. Clinical audit, a valuable tool to improve quality of care: General methodology and applications in nephrology. World J Nephrol. 2014 Nov 6; 3(4):249-255.

3. Wooster D. A Structured Audit Tool of Vascular Ultrasound Interpretation Reports: A Quality Initiative. JVU. 2007; 31(4):207-10.

4. Pereira VC, Silva SN, Carvalho VKS, et al. Strategies for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in public health: an overview of systematic reviews. Health Res Policy Syst [Internet]. 2022;20(1). Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00815-4. Accessed November 16, 2024.

5. Kherani RB, Wooster EM, Wooster DL. CPD for the Busy Rheumatologist: MOC Section 3 Credits: These Can Be Easy. CRAJ. Fall 2023; 33(3):20.

6. Kherani RB, Wooster EM, Wooster DL. CPD for the Busy Rheumatologist: Knowledge Translation: What’s in It for Me? CRAJ. Winter 2023; 33(4):22-23.

7. Kherani RB, Wooster EM, Wooster DL. CPD for the Busy Rheumatologist: Mini-Practice Audit Model (mPAM): Overcoming the “Fear” of Chart Audits. CRAJ. Spring 2024; 34(2):26-27.

8. Wooster DL, Wooster EM, Kherani RB. CPD for the Busy Rheumatologist: Raising the bar of the clinical audit spectrum: A comparison between the Mini-Practice Audit Model (mPAM) and other types of clinical audits. CRAJ. Fall 2024; 34(3):22-23.

9. Keeling SO, Alabdurubalnabi Z, Avina-Zubieta A, et al. Canadian Rheumatology Association Recommendations for the Assessment and Monitoring of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2018; 45(10):1426-1439.

|