Fall 2024 (Volume 34, Number 3)

CPD for the Busy Rheumatologist

Raising the Bar of the Clinical Audit Spectrum:

A Comparison Between the Mini-Practice Audit Model (mPAM) and Other Types of Clinical Audits

By Douglas L. Wooster, MD, FRCSC, FACS, DFSVS, FSVU, RVT, RPVI; Elizabeth M. Wooster, M.Ed, PhD(c); and Raheem B. Kherani, BSc (Pharm), MD, FRCPC, MHPE

Download PDF

“The Royal College said clinical chart audits are important for mandatory Section 3 Credits. . . I looked this up and there are different kinds

. . . some look easier than others!” exclaims Dr. AKI Joint, a rheumatologist member of the Canadian Rheumatology Association (CRA). “I know there have been recent changes to the Maintenance of Certification Guidelines — what do I do?”

A clinical audit is a systematic review of an individual’s or group’s practice with comparison to established “best practice” standards. The audit cycle identifies gaps, promotes change and confirms practice improvement. It should be direct and focus on actual practice in a manner that allows for discrete intervention and change. It is not a practice inventory or a research project to identify “best practice.” It is an audit designed to lead to quality improvement of actual practice. Ideally, gaps should be identified and feedback given to address remedies that can be established in practice. A follow-up re-audit can be done to confirm change in practice.

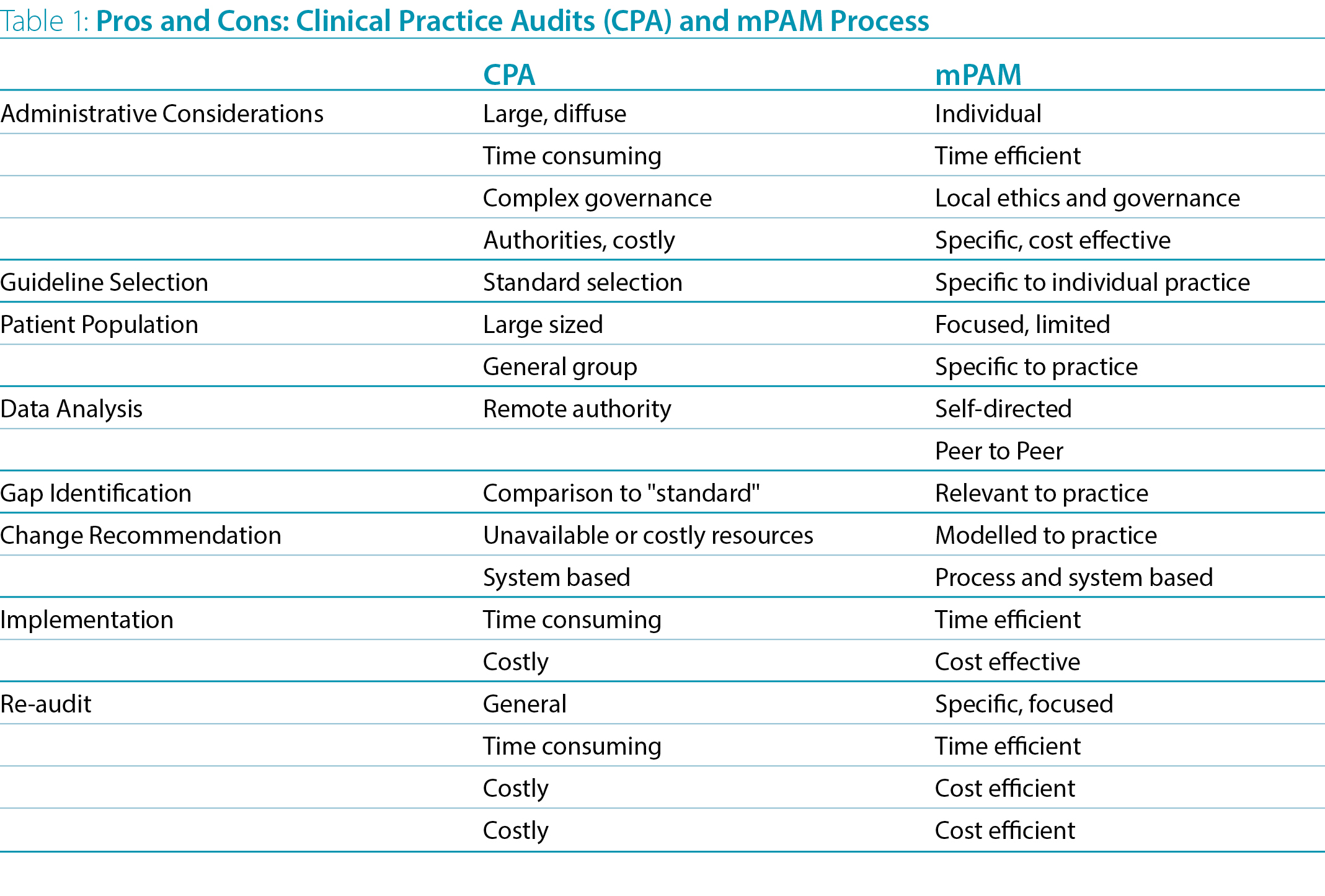

Although administrative and authority-driven audits and 360° reviews have been promoted to identify strengths and weaknesses in physicians’ use of practice guidelines, these are frequently large and expensive and done only occasionally. The chosen guidelines may not be relevant to actual practice. Patient selection may lack specificity and relevance and often demands large numbers of patients or “blind” audits of extensive databases. The information is usually diffuse and not specific to an individual’s practice. Analysis may be done by “experts” and feedback given as a committee’s ”action plan”. This may lead to irrelevant comparisons and, hence, impractical conclusions and recommendations for change. As such, implementation and re-audit may not be practical.

In contrast, the mini-Practice Audit Model (mPAM) (Table 1) uses specific domains and elements directly related to individual practice guidelines, standards or protocols. A limited number of patients (10-20) is often adequate to sample practice patterns. The data can be correlated directly to guidelines, and gaps can be readily identified. It has been shown to directly inform feedback to individual physicians for improvement strategies and specific implementation. It is reliable and relates clearly to actionable interventions, including education and re-audit, and implementation of practice improvement (Wooster 2007).

The cycle of audit, analysis, education/intervention, application, re-audit and re-application used in the mPAM can be used for personal improvement or in a group strategy. It can be documented as a personal learning project or otherwise as a quality improvement activity for recognized CPD credits. The findings and process can also be used for group learning and focused education rounds or courses, or literature review or to search for appropriate definitions and guidelines. Identified deficiencies can also inform further clinical and standards investigation and quality improvement strategies in related areas.

“The mPAM format is one that I could actually do…” says Dr. AKI Joint. “I will be able to select the best approach every six months to actively monitor my own patient charts in my practice (and to get MOC Section 3 credits).”

Douglas L. Wooster, MD, FRCSC, FACS,

DFSVS, FSVU, RVT, RPVI

Professor of Surgery,

Temerty Faculty of Medicine,

University of Toronto

Elizabeth M. Wooster, B.Comm, M.Ed, PhD(c)

OISE/University of Toronto

Research Associate,

School of Medicine,

Toronto Metropolitan University

Raheem B. Kherani, BSc (Pharm), MD, FRCPC, MHPE

CRA Education Committee Past Chair,

Program Director and Clinical Associate Professor,

University of British Columbia

Director, Intensive Collaborative Arthritis Program,

Mary Pack Arthritis Program

Clinician Investigator, Arthritis Research Canada

Division Head, Rheumatology, Richmond Hospital

Rheumatologist, West Coast Rheumatology Associates

Richmond, British Columbia

References:

1. Rose N, Pang SJ. A Practical Guide to Implementing Clinical Audit. Can Vet J. 2021; 62:145-156.

2. Pasquale E, Dal Canton A. “Clinical Audit, a Valuable Tool to Improve Quality of Care: General Methodology and Applications in Nephrology.” World J Nephrol. 2014 Nov 6; 3(4):249-55. doi:10.5527/wjn.v3.i4.249

3. Wooster D. A Structured Audit Tool of Vascular Ultrasound Interpretation Reports: A Quality Initiative. JVU. 2007; 31(4):207-10. doi: 10.1177/154431670703100404.

4. Fasih N, Mason A. The Canadian Association of Radiologists. A Step by Step Guide: Maximizing The Effectiveness Of Clinical Audits. 2011. Available at https://car.ca/wp-content/uploads/CAR-Guide-Clinical-Audit.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2024.

5. Pereira VC, Silva SN, Carvalho VKS, et al. Strategies for the Implementation of Clinical Practice Guidelines in Public Health: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Health Res Policy Syst [Internet]. 2022; 20(1). Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00815-4. Accessed August 13.

6. Kherani RB, Wooster EM, Wooster DL. CPD for the Busy Rheumatologist: MOC Section 3 Credits: These Can Be Easy. CRAJ. Fall 2023; 33(3):20. Available at http://www.craj.ca/archives/2023/English/Fall/Kherani-Wooster-Wooster.php. Accessed October 28, 2024.

7. Kherani RB, Wooster EM, Wooster DL. CPD for the Busy Rheumatologist: Knowledge Translation: What’s in It for Me? CRAJ. Winter 2023; 33(4):22-23. Available at http://www.craj.ca/archives/2023/English/Winter/Kherani-Wooster-Wooster.php. Accessed October 28, 2024.

8. Kherani RB, Wooster EM, Wooster DL. CPD for the Busy Rheumatologist: Mini-Practice Audit Model (mPAM): Overcoming the “Fear” of Chart Audits. CRAJ. Spring 2024; 34(3): 26-27. Available at http://www.craj.ca/archives/2024/English/Spring/Kherani-Wooster-Wooster.php. Accessed October 28, 2024.

|