Spring 2021 (Volume 31, Number 1)

MIS-C and PIMS:

The Alphabet Soup of

COVID-associated

Hyperinflammation in Children

By Tala El Tal, MD; and Rae S. M. Yeung, MD, FRCPC, PhD

Download PDF

Patient Case:

An eight-year-old previously healthy South Asian boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with four days of persistent

fever, abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea, associated with bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis, rash over his chest,

lower limbs and palms, and red swollen cracked lips. Four weeks prior to presentation, his father tested positive for severe

acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) on nasopharyngeal swab. At the time, the patient was asymptomatic

and was not tested. On arrival to ED, he was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 78/47 mm Hg and heart rate of 150 beats/

min despite receiving 40 mL/kg of fluid. Peripherally, he was cool to touch and had prolonged capillary refill.

Laboratory results on admission were significant for markedly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), thrombocytopenia,

lymphopenia, hyperferritinemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypertriglyceridemia, elevated liver enzymes, coagulopathy, and

markedly elevated troponin I and

N-terminal-pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). An echocardiogram (ECHO)

showed reduced left ventricular systolic function and dilated left anterior descending artery. An electrocardiography

(ECG) showed diffuse non-specific T-wave abnormalities. The patient’s nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 was indeterminate

on repeated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, but serology testing for COVID-19 IgG antibody was reactive.

He was diagnosed with multisystem inflammatory system in children (MIS-C), also known as pediatric inflammatory

multisystem syndrome (PIMS) temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) where

he required inotropic support for his cardiac dysfunction. He was given IVIG and steroids as immunosuppressive agents

to control his hyperinflammation together with anti-platelet doses of ASA. He improved dramatically requiring only a

4-day hospital stay with the first two in the ICU. He was discharged on a three-week course of weaning steroids with full

recovery and no long-term adverse cardiovascular consequences.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was

thought that most children were either asymptomatic

or had mild disease manifestations. Beginning in

April 2020, clinicians at COVID-19 epicenters observed

the emergence of clusters of school-aged children with fever

and features of Kawasaki Disease (KD) and toxic shock

syndrome (TSS) following COVID-19 in their communities.

Alerts were issued to the medical community and various

different names and case definitions were proposed (visit

cps.ca/en/documents/position/pims for more information).1

For the purpose of this article, the term MIS-C will be used.

This brief update will focus on three practical questions:

- When to suspect MIS-C?

- How to approach the diagnostic evaluation of MIS-C?

- How to treat MIS-C?

When to suspect MIS-C?

The signs and symptoms of MIS-C can largely overlap with

Kawasaki Disease and toxic shock syndrome (TSS). KD is

a hyperinflammatory syndrome presenting as acute multisystem

vasculitis affecting young children. The principal

features include: (1) bilateral conjunctival injection; (2)

polymorphous skin rash; (3) erythema and edema of the

hands and/or feet; (4) cervical lymphadenopathy; and (5)

oral mucosal changes, in the presence of at least 5 days

of fever. KD is known to have a predilection for the coronary

arteries, leading to aneurysm formation in 25% of

untreated cases.2

Similarly, children with MIS-C present with persistent fevers

and multi-organ dysfunction (cardiac, hematologic, gastrointestinal,

neurological, renal, and/or dermatologic) usually

3-6 weeks following prior SARS-COV-2 exposure,3,4

suggesting post-infectious hyperinflammation underlying

the pathobiology.5 Like KD, MIS-C is a syndrome complex

with a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes. A spectrum

of COVID-19 associated hyperinflammation syndromes

has been proposed6,7 with three clinical patterns along the

hyperinflammation spectrum in MIS-C: Shock, KD, and

fever with inflammation, reflecting the continuum of disease

severity. Early reports were notable for myocarditis, myocardial dysfunction and overt shock requiring inotropic

support as prominent clinical features. Some patients

developed coronary aneurysms, as well as macrophage activation

syndrome (MAS). It was also observed that MIS-C

typically affects healthy children and disproportionately

affects non-Caucasian children, with children from African,

Hispanic and South Asian ethnicity being more affected.

It remains unclear the contribution of environment

versus genetics, with higher rates of COVID-19 noted in

affected communities.

How to approach the diagnostic evaluation of

MIS-C?

A high-index of suspicion for the diagnosis of MIS-C is needed

in children living in COVID-19 hotspots, who present

with prolonged fever and clinical and laboratory features

of inflammation. MIS-C is usually preceded by known

SARS-CoV-2 infection in the child or a family member

several weeks before presentation. Children may present

with features of KD and/or TSS, and often abdominal pain

and other gastrointestinal features are prominent. Of note,

MIS-C is a diagnosis of exclusion and other causes of febrile

illness in children, including other infectious and non-infectious

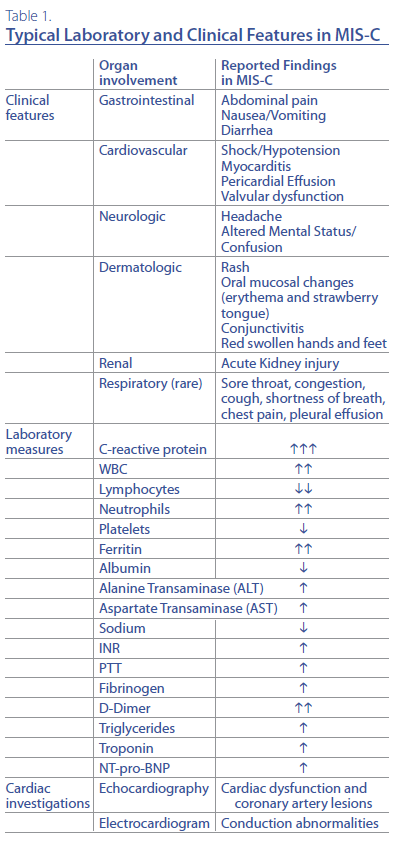

etiologies need to be pursued. Table 1 summarizes

the typical laboratory and clinical findings reported

in MIS-C. Patients have evidence of a hyperinflammatory

state, manifested in laboratory findings of markedly elevated

CRP, and measures compatible with viral infection

(lymphopenia) and MAS including thrombocytopenia and

elevated serum ferritin,6 which together with hyponatremia,

elevated troponin and NT-pro-BNP, are among the

worrisome laboratory findings suggestive of a more severe

disease phenotype.8

How to treat MIS-C?

Although there is rapidly growing literature on MIS-C, management

has been largely based on extrapolated knowledge

from KD treatment. Several groups have convened

expert panels to develop guidance including the American

College of Rheumatology (ACR), which developed guidelines

for the evaluation and treatment of MIS-C.8 Children

admitted to hospital with MIS-C should be managed

by a multi-disciplinary team including rheumatology,

cardiology and other subspecialties as needed. The cornerstone

of therapy is immunomodulation. Treatment recommended

for all children requiring hospitalization for

MIS-C involves step-wise progression of immunosuppression,

starting with high-dose IVIG (2 g per kg per dose)

as first-line therapy. Adjunctive therapy with low-moderate

dose glucocorticoid therapy (prednisone 1-2 mg/kg/d) is

recommended in patients with severe disease, at high-risk

for poor coronary outcome, or as therapy for IVIG failure.

In patients who present with critical organ involvement requiring

inotropic support, or those who are recalcitrant

to IVIG and low-moderate dose steroids, high-dose, pulse

glucocorticoids (10-30 mg/kg/d) are recommended. IL-1

blockers, such as Anakinra (> 4 mg/kg/d), may be considered

in those with disease refractory to IVIG and steroid

therapy, as well as those with features of MAS. Close follow-

up with serial laboratory and cardiac assessment will

help guide duration and tapering of immunosuppression,

with a typical steroid wean over a minimum of 2-3 weeks,

and often longer given the high rate of rebound inflammation

with quicker tapers.8 Other immunomodulatory treatments

have been used and reported in the literature including tocilizumab (IL-6 inhibitor) and infliximab (TNF

inhibitor)9,10 but insufficient data exists for clear recommendations.

Similar to KD, MIS-C patients are treated with

anti-platelet low dose aspirin (ASA) (3-5 mg per kg per day)

as thromboprophylaxis. Anticoagulation with enoxaparin

should be considered in MIS-C patients with coronary artery

aneurysms as per KD management guidelines and in

those with moderate-severe left ventricular dysfunction

(Ejection Fraction < 35%).8

Serial monitoring of clinical and laboratory parameters,

including ECG and ECHO, are recommended as part of the

comprehensive follow up post-discharge.

In summary, MIS-C is a post-infectious hyperinflammatory

syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2

infections affecting children. There is a wide spectrum of

disease with many sharing features with KD and the most

severely affected children presenting with cardiogenic

shock and MAS. Immunomodulation is the foundation of

therapeutic management, with most children responding

rapidly to treatment. MIS-C remains a rare complication of

SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Rae S. M. Yeung, MD, FRCPC, PhD

Hak-Ming and Deborah Chiu Chair in

Paediatric Translational Research

Professor of Paediatrics, Immunology & Medical Science

University of Toronto

Senior Scientist and Staff Rheumatologist,

The Hospital for Sick Children

Toronto, Ontario

Tala El Tal, MD

Division of Rheumatology

The Hospital for Sick Children

Toronto, Ontario

References and Suggested Readings:

1. Berard RA, Scuccimarri R, Haddad EM, et al Paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally

associated with COVID-19. Ottawa: Canadian Paediatric Society; 2020 July 6. Available at

www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/pims. Accessed February 2021.

2. McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management

of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American

Heart Association. Circulation. 2017; 135(17):e927-e999.

3. Soma VL, Shust GF, Ratner AJ. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Curr Opin Pediatr.

2021; 33(1):152-158. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000974. PMID: 33278107.

4. Kabeerdoss J, Pilania RK, Karkhele R, et al. Severe COVID-19, multisystem inflammatory syndrome

in children, and Kawasaki disease: immunological mechanisms, clinical manifestations and management.

Rheumatol Int. 2021; 41:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04749-4.

5. Henderson LA, Yeung RSM. MIS-C: early lessons from immune profiling. Nat Rev Rheumatol.

2021; 17:75–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-00566-y.

6. Ahmed M, Advani S, Moreira A, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A systematic

review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020; 26:100527. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100527. Epub

2020 Sep 4. PMID: 32923992; PMCID: PMC7473262.9.

7. Yeung RS, Ferguson PJ. Is multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children on the Kawasaki

syndrome spectrum? J Clin Invest. 2020; 130(11):5681-5684. doi: 10.1172/JCI141718. PMID:

32730226; PMCID: PMC7598074.

8. Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, et al. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance

for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and

Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 1. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020; 72(11):1791-

1805. doi: 10.1002/art.41454. Epub 2020 Oct 3. PMID: 32705809; PMCID: PMC7405113.

9. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al. Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators; CDC COVID-19

Response Team. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in U.S. Children and Adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(4):334-346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. Epub 2020 Jun 29. PMID:

32598831; PMCID: PMC7346765.

10. Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 58 Children With a Pediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome Temporally Associated With SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020; 324(3):259-269. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.10369

|