Spring 2019 (Volume 29, Number 1)

Facilitating Physical Activity Prescription

by Medical Professionals with

Open-access Web-based Resources

By Derin Karacabeyli; Kaila Holtz, MD, MSc; and Kam Shojania, MD, FRCPC

Download PDF

Introduction

Physical inactivity is a global public health problem,1 and

regular exercise is one of the most powerful modifiable risk

factors for the prevention and management of chronic disease.2 Regular physical activity has been shown to reduce

the incidence of cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension,

type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, and premature

all-cause mortality.3 In patients with inflammatory arthritis

and osteoarthritis, regular physical activity improves

function, reported pain, and quality of life.4,5 Despite the

abundant evidence supporting the role of regular physical

activity in the prevention and management of chronic disease,

inactivity remains the norm. As of 2013, 78% of Canadian

adults and 91% of youth were not meeting the guidelines

of 150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise and two

strength training sessions per week.6

While patients are more likely to exercise if physical activity

is addressed by their healthcare provider,7 exercise

prescription in the clinical setting has its challenges. Busy

clinicians report barriers such as lack of time, knowledge,

training, and resources.8,9 With www.ExRxMed.com, we hope

to empower all physicians to ask every patient at every visit

about physical activity in an individualized, time-efficient

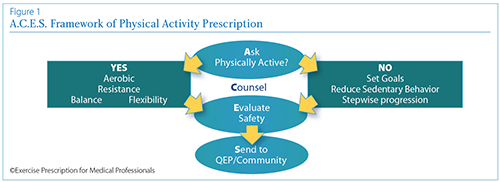

manner. An Overview of the A.C.E.S Framework for discussing

physical activity is shown below (Figure 1).

1) Ask about physical activity.

Start the conversation about physical activity using

non-judgmental language and open-ended questions:

“What do you like to do that is physically active?”

An online physical activity vital sign calculator is integrated

into the website, and we encourage clinicians to

send this to their patients in advance via email. It generates

a printable PDF report that can serve as the basis for your

conversation about physical activity if time permits.

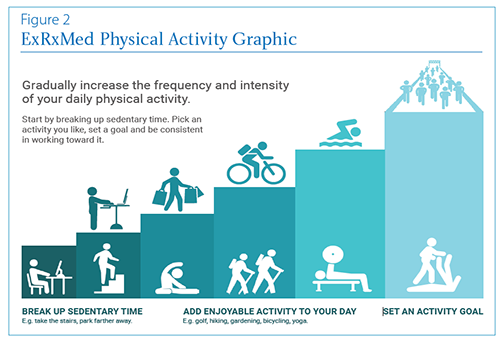

2) Counsel individuals to reduce sedentary time.

If patients are inactive, the first priority is counseling to

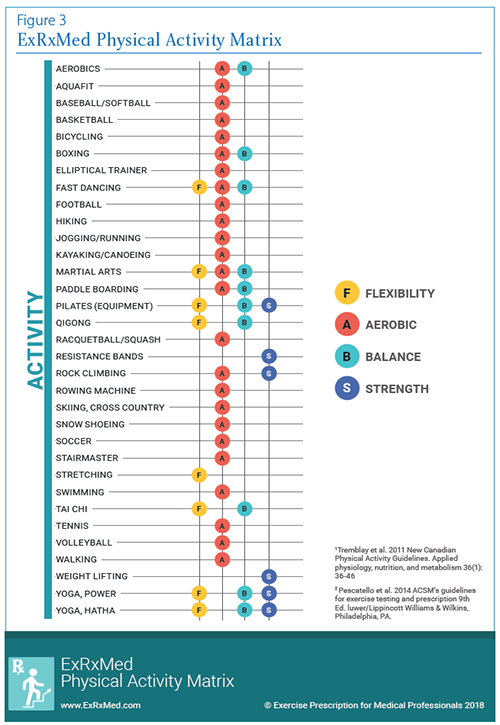

reduce sedentary time (Figure 2). If patients are somewhat

active and motivated, add balance, strength, or flexibility

activities (Figure 3). We have created two resources that illustrate

a simple, step-wise, and safe approach to gradually

increasing the frequency, intensity, and variety of weekly

physical activity.

3) Evaluate for safety.

We have included a link to the “Get Active Questionnaire”10

to enable physicians to screen for patients who may need

further cardiorespiratory investigations prior to engaging

in moderate-to-vigorous exercise.

4) Send to a qualified exercise

professional (QEP), if necessary.

There is a referral form available to encourage

patients to find a qualified exercise professional

to assist them in achieving their goals.

We have listed several Canadian resources and

hope to expand this resource in the future.

Finally, there is a link to the Exercise is

Medicine Physical Activity Prescription Pad

for clinicians who wish to complete a formal

prescription for their patients. Our resources

are meant to be used in combination. We

encourage physicians to incorporate them

into clinical practice in a manner that suits

their workflow, patient population, and

available resources.

Conclusion

Physical activity serves as an invaluable pillar

in the prevention and management of many

chronic diseases, as well as in the enhancement

of quality of life. We have adapted the

five A’s model of behaviour counseling11 to

develop a web-based tool aimed at minimizing

commonly reported barriers to physical

activity prescription. Next steps will involve

validation of our tool through formal research

to evaluate the impact and outcomes

of web-based counseling tools on physician

and patient behaviours. Please contact us if

you are interested in collaborating by visiting

www.ExRxMed.com.

References:

1. World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health: Physical Activity.

Available at http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/pa/en/. Accessed November 3, 2018.

2. Naci H, Loannidis JP. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality

outcomes: Metaepidemiological study. BMJ 2013; 347:f5577.

3. Warburton DE, Charlesworth S, Ivey A, et al. A systematic review of the evidence for Canada’s

Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010; 7:39.

4. Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, et al. Exercise for osteoarthrtitis of the knee: a Cochrane

systematic review B J Sports Med 2015; 49:1554-57.

5. Metsios GS, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Kitas GD. The role of exercise in the management of

rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2015; 11:1121-30.

6. Public Health Agency of Canada. How Healthy Are Canadians? A trend analysis of the health of

Canadians from a healthy living and chronic disease perspective. Available at https://www.cana

da.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/how-healthy-canadians/

pub1-eng.pdf. Published April 11, 2017. Accessed November 3, 2018.

7. Grandes G, Sanchez A, Sanchez-Pinilla RO, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity advice and

prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med

2009; 169:694-701.

8. Hoffmann TC, Maher CG, Briffa T, et al. Prescribing exercise interventions for patients with chronic

conditions. CMAJ 2016; 188:510-18.

9. Hébert ET, Caughy MO, Shuval K. Primary care providers’ perceptions of physical activity counselling

in a clinical setting: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2012; 46:625-31.

10. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Get Active Questionnaire. Available at http://www.csep.

ca/en/publications/get-active-questionnaire. Accessed November 5, 2018.

11. Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, et al. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions:

an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med 2002; 22:26-84.

Derin Karacabeyli

Faculty of Medicine

University of British Columbia

Vancouver, British Columbia

Kaila Holtz, MD, MSc

Faculty of Medicine

Division of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

University of British Columbia

Vancouver, British Columbia

Kam Shojania, MD, FRCPC

Clinical Professor and Head,

UBC Divison of Rheumatology

Medical Director,

Mary Pack Arthritis Program

Vancouver, British Columbia

|