Spring 2018 (Volume 28, Number 1)

CreaTe Central Access and Triage Improves Access to Care for Albertans

By Dianne Mosher, MD, FRCPC

Download PDF

CreaTe central access and triage was instituted in Calgary in 2007 as part of an innovations grant through the government of Alberta. Central access and triage is a single intake point for rheumatology referrals at the University of Calgary serving a population of approximately 2 million people in Southern Alberta. Since its inception in 2007, over 65,000 patients have been triaged and we continue to meet the Canadian Wait Time Alliance benchmark for early inflammatory arthritis of 4 weeks.

Nineteen rheumatologists are part of this program. The triage nurse reviews all referrals, prioritizes the referral and facilitates appointments to the first available provider. All referrals are entered and tracked in a database. Specialized clinics were established to expedite the care of more urgent patients. Referrals that are not accepted or where the triage category is unclear are reviewed by a physician.

The objective is to manage our wait list more effectively by using one central intake, eliminating duplicate referrals and prioritizing the most urgent patients first.

A study by Hazlewood1 showed that at two years, the variability of wait times for rheumatologists decreased, wait times for urgent and moderate referrals were reduced, the quality of referrals improved, and there were no duplicate referrals. At seven years follow up, wait times for urgent and moderate referrals were controlled despite a growing population.

Today we receive 500-600 referrals a month and we have a wait list of over 1,200 patients.

Capacity issues are being addressed by Stable Rheumatoid Arthritis clinics, a partnership with our primary care networks which provides telephone advice via a specialist link, and care pathways developed for gout and osteoarthritis (OA) incorporating the AAC-CFPC OA Tool. Key performance indicators have been developed for central intake to insure we are improving accessibility to rheumatology care for Albertans.2

Dr. Dianne Mosher, Professor of Medicine, Division Head,

Rheumatology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

References:

1. Hazlewood GS, Barr SG, Lopatina E, et al. Improving appropriate access to care with central referral and triage in rheumatology. Arthritis Care & Research 2016; 68(10):1547–53.

2. Barber CE, Patel JN, Woodhouse L, et al. Development of key performance indicators to evaluate centralized intake for patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:322.

|

|

|

Strategic Clinical Networks

By Dianne Mosher, MD, FRCPC; and Joanne Homik, MD, FRCPC

Download PDF

Alberta’s 15 Strategic Clinical Networks (SCNs) were created to engage healthcare workers, patients, researchers and administrators to find new and innovative ways to deliver care and provide improved clinical outcomes and better quality care with demonstrated cost effectiveness.

The Bone and Joint Health Strategic Clinical Network (BJH SCN) is Alberta’s primary vehicle for provincial bone and joint strategies that aim to keep Albertans healthy, provide high-quality care when they are sick, ensure they have access to care when they need it, and improve their journey through the health system. In Alberta, someone enters a doctor’s office every 60 seconds seeking treatment for a bone or joint problem. This rate of demand will only increase as Alberta’s population grows, ages and lives longer. The BJH SCN will help manage and reduce the impact of bone and joint health issues on our system while improving patient care.

Key successes include a reduction in hospital stay for hip and knee replacement from 4.7 to 3.8 days, the introduction of 13 physiotherapy clinics delivering the GLA:D program (Good Living with osteoArthritis: Denmark), and screening 14,455 Albertans with signal fracture for osteoporosis.

The Arthritis Working Group of the SCN has identified two key factors for improving care for patients suffering from Inflammatory Arthritis (IA) in Alberta: (1) increase capacity for care, and (2) decrease disparity in clinical care and outcomes. Both were addressed in a shared care model for IA and an accompanying measurement framework. Presently three successful models are being evaluated for key learnings: (1) The nurse-led clinical team at South Health Campus; (2) On-TRAAC program in Edmonton; and (3) Telemedicine program in Pincher Creek. These clinics provide exemplary cases of shared care that should be replicated to improve access and reduce disparities.

Dr. Dianne Mosher, Professor of Medicine, Division Head,

Rheumatology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

Dr. Joanne Homik, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine,

Division of Rheumatology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

|

|

|

Extended-Role Practitioners Improve Access to Care for Ontarians

By Katie Lundon, BSc (PT), MSc, PhD; Vandana Ahluwalia, MD, FRCPC; and Rachel Shupak, MD, FRCPC

Download PDF

Since its inception in 2005, the Advanced Clinician Practitioner in Arthritis Care (ACPAC) Program1 (acpacprogram.ca) has successfully graduated 69 extended-role practitioners (ERPs) practising across Canada. It is an Ontario-based, formal, post-licensure training program for appropriately chosen health care providers already experienced in arthritis care that ensures acquisition of the advanced skills and knowledge necessary to support the development of extended practice roles.

Utilization of ACPAC ERPs in interprofessional shared-care models of arthritis management has optimized scarce human health resources in rheumatology and has specifically achieved success at the system level as follows:

- Excellent agreement between an ACPAC-trained ERP and rheumatologist in independently determining inflammatory arthritis (IA) vs non-inflammatory disease, and improved access to rheumatologist care with a 40% reduction in time-to-treatment decision.2

- Centralized paper triage of rheumatology referrals by an ACPAC ERP reduced wait times for patients with suspected IA by more than 50% (15.5 days) compared to the traditional rheumatologist model of care (33.8 days).3

- Triage by an ACPAC ERP resulted in a high number of patients with suspected IA/connective tissue disease being correctly prioritized for a rheumatology consultation with wait times decreased to below the provincial median.4

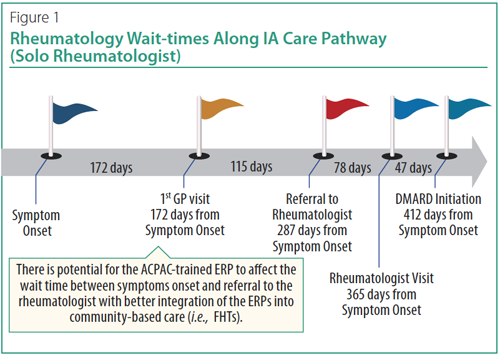

In summary, an ACPAC-trained and experienced ERP can shorten the time-to-rheumatologist assessment (Figure 1) allowing an earlier diagnosis and treatment decision for patients with IA.2 ACPAC ERPs, with some evolution in policy, could plausibly be even better positioned at the community level (e.g., Family Health Team) to identify and triage patients with suspected IA for expedited referral to a rheumatologist (Figure 1).

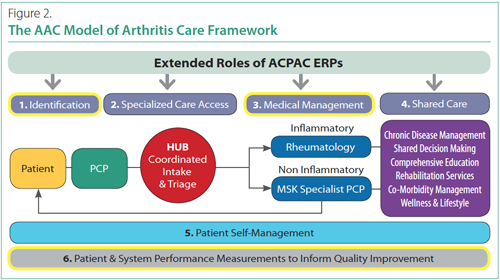

A trained ERP can be positioned at multiple points to support identification, access, medical management and shared care in accordance with the Arthritis Alliance of Canada (AAC) model of arthritis care framework (Figure 2).

Dr. Katie Lundon, Program Director, Advanced Clinician Practitioner

in Arthritis Care (ACPAC) Program, Office of Continuing Professional

Development, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON

Dr. Vandana Ahluwalia, former Corporate Chief of Rheumatology,

William Osler Health System, Brampton, ON

Dr. Rachel Shupak, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine,

University of Toronto; Physician, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON

References:

1. Lundon K, Shupak R, Schneider R, et al. Development and early evaluation of an inter-professional post-licensure education programme for extended practice roles in arthritis care. Physiotherapy Canada 2011; 63:94-103.

2. Ahluwalia V, Larsen T, Lundon K, et al. An advanced clinician practitioner in arthritis care can improve access to rheumatology care in community-based practice. Manuscript submitted, 2017.

3. Farrer C, Abraham L, Jerome D, et al. Triage of rheumatology referrals facilitates wait time benchmarks. J Rheumatol 2016; 43:2064-67.

4. Bombardier C, et al. The Effect of triage assessments on identifying inflammatory arthritis and reducing rheumatology wait times in Ontario [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68 (suppl 10). Available at acrabstracts.org/abstract/the-effect-of-triage-assessments-on-identifying-inflammatory-arthritis-and-reducing-rheumatology-wait-times-in-ontario/. Accessed March 7, 2018.

|

|

|

Rheumatology Nurses Improve Access to Care in British Columbia

By Michelle Teo, MD, FRCPC

Download PDF

In 2011, BC rheumatologists were awarded funds for integration of nurses into patient care. From that, the Multidisciplinary Conference fee schedule (“Nursing code” as we affectionately refer to it) was born. The “Nursing code,” which can be billed every six months per patient, allows a rheumatologist to hire a Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) or Registered Nurse (RN) to support the management of patients with inflammatory arthritis. The nurses provide a wide variety of services to patients, including disease and medication counselling, methotrexate and biologic injection training, vaccine administration and tuberculosis skin testing.

Rheumatology nurses not only allow us to provide enhanced care to our patients, but can also improve access to care in underserviced areas. Some nurses work in an interdisciplinary care model, where side by side with the rheumatologist they provide care for new and follow-up patients. This approach has improved patient access by reducing wait times for new referrals and has allowed follow-up patients to be seen more promptly when needed.

During 2016-2017, 53 of the 86 rheumatologists in BC used the “Nursing code,” with an estimated 55 rheumatology nurses employed across the province. We celebrate the success of this programme and it is with excitement that we enter this new era, where established rheumatologists and new graduates alike realize the power of integrating allied health, such as nursing, into the modern day rheumatology practice.

Dr. Michelle Teo, Rheumatologist, Balfour Medical Clinic,

Penticton BC; Clinical Instructor, Department of Medicine,

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC

|

|

|

Family Physicians with Extended Scope of Practice Improve Access to Care in Nova Scotia

By Evelyn Sutton, MD, FRCPC, FACP

Download PDF

In response to an acute shortage of rheumatologists in Nova Scotia in 2011, an innovative new Collaborative Care Clinic was launched in Halifax to expand access and services for patients with inflammatory arthritis. The clinic was based on a multidisciplinary model of care tailored to meet regional needs. A local family physician completed a six-month training program in rheumatology and then worked alongside a team of experienced rheumatology nurses, physiotherapists and a rheumatologist in the Collaborative Care Clinic.

After the clinic had been operational for three years, an independent research firm was contracted to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the model. The most important lesson learned was that success relied on having buy-in from everyone involved in the clinic. Booking clerks had not been included in the initial discussions when setting up the clinic, and the result was that they tended to book stable inflammatory arthritis patients with the rheumatologist rather than with the collaborative care team, thinking this was ‘preferred.’ Once they understood the rationale for the triage model and were exposed to the positive ratings from patient satisfaction questionnaires, clinic bookings improved dramatically.

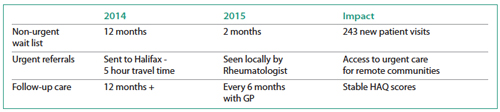

HAQ—Health Assessment Questionnaire

The model was expanded to Cape Breton in 2015, where two family physicians were trained to work alongside a rheumatologist and one continues in this role. A quality assessment conducted after just one year showed impressive improvements in wait times and better utilization of scarce rheumatology resources.

A prospective study is now underway to examine patient satisfaction, disease outcomes, and patient self-perception of pain management among patients cared for within the Collaborative Care Clinic compared to those followed in usual care (i.e., by a rheumatologist who works in a hospital outpatient clinic).

Dr. Evelyn Sutton, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine,

Division of Medical Education, Halifax, NS

Reference:

1. Hickcox S. Rheumatology Care Re-designed, Models of Care in Action: You can do it too! Workshop held at the 2017 Canadian Rheumatology Association annual meeting. Ottawa. 2017.

|

|

|

Videoconferencing and Interprofessional Support Can Improve Access to Care in Saskatchewan

By Regina Taylor-Gjevre, MSc, MD, FRCPC; Bindu Nair, MSc, MD, FRCPC; Brenna Bath, BScPT, MSc, PhD; Udoka Okpalauwaekwe, MD, MPH; Meenu Sharma, MSc; Erika Penz, MD, MSc, FRCPC; Catherine Trask, PhD; and Samuel Alan Stewart, PhD

Download PDF

A relatively high proportion of the Saskatchewan population resides in smaller communities and rural areas. Travel to access rheumatology follow-up and care for people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in these areas may be challenging. There have been several reports of utilization of telehealth in the provision of rheumatology consultation. Our group undertook a study supported with research funding from the Canadian Initiative for Outcomes in Rheumatology care (CIORA), to evaluate whether RA patients followed longitudinally, using videoconferencing and interprofessional care support, have comparable disease control to those followed in traditional in-person rheumatology clinics.

A total of 85 RA patients were allocated to either traditional in-person rheumatology follow-up or video-conferenced follow-up with urban-based rheumatologists and rural in-person physical therapist examiners. Follow-up was every three months for nine months. Outcome measures included disease activity metrics (DAS-28CRP, RA disease activity index [RADAI]), modified health assessment questionnaire (mHAQ), quality of life (EQ5D), and patient satisfaction (VSQ9).

We found no evidence of a difference in effectiveness between interprofessional videoconferencing care and traditional rheumatology clinic for both provision of effective follow-up care and patient satisfaction for established RA patients. High drop-out rates in both groups reinforced the need for consideration of patients’ needs and preferences in developing models of care. While use of videoconferencing/telehealth technologies may be a distinct advantage for some patients, there may be loss of travel-related auxiliary benefits for others.

Dr. Regina Taylor-Gjevre, Division of Rheumatology, College of

Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Dr. Bindu Nair, Division of Rheumatology, College of Medicine,

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Dr. Brenna Bath, School of Physical Therapy, University of

Saskatchewan; Canadian Centre for Health and Safety in Agriculture,

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Dr. Udoka Okpalauwaekwe, Division of Rheumatology, College of

Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Ms. Meenu Sharma, Canadian Centre for Health and Safety in

Agriculture, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Dr. Erika Penz, Division of Respirology, College of Medicine, University

of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Dr. Catherine Trask, Canadian Centre for Health and Safety in

Agriculture, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Dr. Samuel Alan Stewart, Medical Informatics, Department of

Community Health & Epidemiology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS

Reference:

Taylor-Gjevre R, Nair B, Bath B, et al. Addressing rural and remote access disparities for patients with inflammatory arthritis through video-conferencing and innovative inter-professional care models. Musculoskeletal Care 2018; 16(1):90-5.

|

|

|

|